NASA Seeks to PEP Up Shuttle/Spacelab (1981)25 March 2017 David S. F. Portree

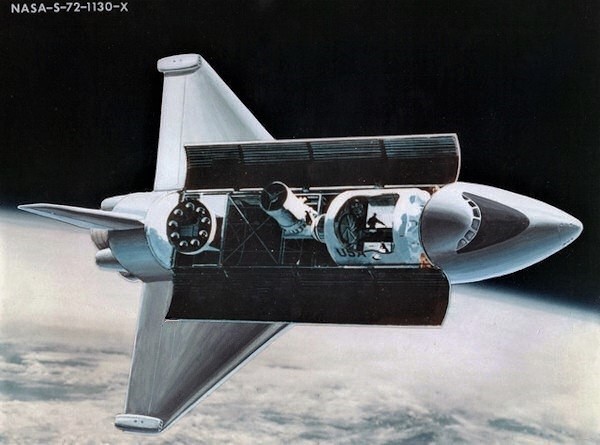

Early artist concept of the Space Shuttle Orbiter with a cutaway of the "Sortie Lab" near the front of its Payload Bay. At this point in its history, the Sortie Lab was expected to be manufactured by a U.S. aerospace contractor. The Sortie Lab depicted is dedicated at least partly to astronomy, as evidenced by the large telescope attached to the aft end of the Sortie Lab pressurized module. Image credit: NASA

Early artist concept of the Space Shuttle Orbiter with a cutaway of the "Sortie Lab" near the front of its Payload Bay. At this point in its history, the Sortie Lab was expected to be manufactured by a U.S. aerospace contractor. The Sortie Lab depicted is dedicated at least partly to astronomy, as evidenced by the large telescope attached to the aft end of the Sortie Lab pressurized module. Image credit: NASAOn 29 November 1972, NASA Administrator James Fletcher abolished the Space Station Task Force formed in early 1969 by his predecessor, Thomas Paine, and formed the Sortie Lab Task Force. The "sortie lab," a concept that emerged during Phase B Space Station planning in 1970, was envisioned as a pressurized laboratory module which would be carried in the Shuttle Orbiter's payload bay.

Fletcher's move acknowledged that the Space Shuttle, conceived originally as a vehicle for transporting crews and cargoes between Earth and an Earth-orbiting space station at low cost, would need to become a space station - or, at least, an interim space laboratory that could demonstrate that a space station would be a desirable new goal after the Space Shuttle became operational.

Strapped for funds and encouraged by President Richard Nixon to use spaceflight as a vehicle for international cooperation, NASA asked the European Space Research Organization (ESRO), a predecessor of the European Space Agency (ESA), to provide the sortie lab in exchange for European astronaut flights on board the Shuttle. In August 1973, ESRO and European aerospace contractors agreed to build the sortie lab, which became known as Spacelab.

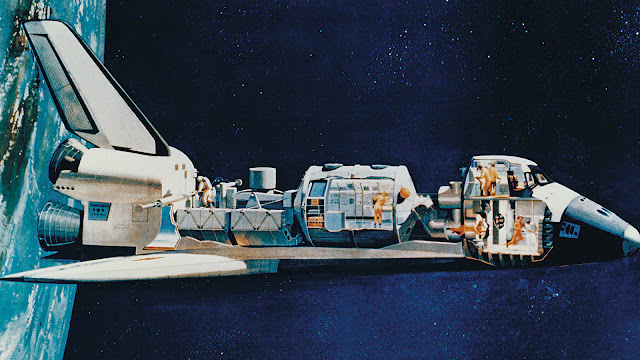

Cutaway illustration of a drum-shaped, ESA-built Spacelab module (center) with a pair of U-shaped Spacelab pallets (left). A bent tunnel with an airlock on top for spacewalks (note space-suited astronaut atop pallet at left) links Spacelab with the Shuttle Orbiter's Mid-Deck, the main living space for the crew. Above that is the Flight Deck, the Orbiter's cockpit. Image credit: NASA

Cutaway illustration of a drum-shaped, ESA-built Spacelab module (center) with a pair of U-shaped Spacelab pallets (left). A bent tunnel with an airlock on top for spacewalks (note space-suited astronaut atop pallet at left) links Spacelab with the Shuttle Orbiter's Mid-Deck, the main living space for the crew. Above that is the Flight Deck, the Orbiter's cockpit. Image credit: NASASpacelab would provide scientists with ample pressurized volume in which to conduct research, but it would rely on limited resources - for example, electricity - provided by the Shuttle Orbiter. Orbiter electricity came from a trio of liquid oxygen/liquid hydrogen fuel cells that could together generate 21 kilowatts continuously for just seven days. Of this, 14 kilowatts were required for Orbiter systems. The Orbiter could thus supply only seven kilowatts to Spacelab. Of these seven kilowatts, between two and five kilowatts would be needed for basic Spacelab systems, leaving a paltry two to five kilowatts for Spacelab experiments.

In 1978, NASA's Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas, launched the Orbital Service Module Systems Analysis Study, which looked into ways that the Space Shuttle Orbiter could be augmented to enable it to better support Spacelab research. An early product of the study was the Power Extension Package (PEP) concept.

Stowed PEP components in the Space Shuttle Orbiter Payload Bay, between the front of a Spacelab module (right) and the rear of the Orbiter crew cabin. Image credit: NASA

Stowed PEP components in the Space Shuttle Orbiter Payload Bay, between the front of a Spacelab module (right) and the rear of the Orbiter crew cabin. Image credit: NASA The PEP deployed in orbit. PEP displays and controls were meant to be located on the Shuttle Orbiter Flight Deck. Image credit: NASA

The PEP deployed in orbit. PEP displays and controls were meant to be located on the Shuttle Orbiter Flight Deck. Image credit: NASAThe PEP concept was linked with NASA's extensive efforts in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Energy to justify the construction of enormous Earth-orbiting Solar Power Satellites (SPSs). It was portrayed as an experience-building experimental test-bed for SPS technology in the Von Karman Lecture JSC director Christopher Kraft presented to the 15th meeting of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics in July 1979. PEP may also have been conceived as a rival for NASA Marshall Space Flight Center's Power Module (see "More Information" below).

The PEP Project Office (PEPPO) at JSC pitched the PEP in a brief report published one month before the first Space Shuttle flight (STS-1 - 12-14 April 1981). The PEPPO envisioned the PEP as a "kit" that could be installed easily in the Shuttle Orbiter payload bay over the tunnel that would link the Orbiter Mid-Deck with the Spacelab.

One hour after launch from Earth, an astronaut on the Flight Deck would use the Canada-built Remote Manipulator System (RMS) robot arm to grapple the PEP's Array Deployment Assembly (ADA) and extend it out over the Orbiter's side. The ADA would then unroll a pair of lightweight solar array wings that together would measure more than 100 feet wide. PEP deployment would require about 30 minutes.

The PEP arrays would track the Sun automatically no matter how the Orbiter became oriented, so almost no astronaut intervention would be needed after they were deployed. The RMS and arrays would be sufficiently sturdy to remain deployed during Orbiter attitude-control maneuvers, but the crew would need to stow them before Orbital Maneuvering System burns lest the acceleration cause damage.

The twin arrays would generate a total of 26 kilowatts of electricity. A cable built into the RMS would carry the electricity from the ADA to the PEP's Power Regulation and Control Assembly (PRCA) in the payload bay. The PRCA would then distribute it to the Orbiter's electrical system.

The three Orbiter fuel cells would "idle" while the PEP arrays were in sunlight. Each would generate one kilowatt of electricity, bringing the total available on board to 29 kilowatts. Fifteen kilowatts would be available for Spacelab, of which between 10 and 13 kilowatts could be devoted to experiments.

Keeping the Spacelab electricity supply constant throughout each 90-minute orbit of the Earth would require that Orbiter fuel cell output ramp up rapidly from three to 29 kilowatts as the PEP arrays passed into darkness over Earth's night side. To achieve this output, each fuel cell would need to exceed its normal maximum by nearly three kilowatts. The fuel cells would then return to their idle state as the PEP arrays passed again into sunlight. Although it would almost certainly place unusual demands on the Orbiter fuel cells, the PEPPO judged this approach to be "feasible."

A PEP could extend Orbiter/Spacelab endurance in Earth orbit to 11 days, the PEPPO estimated. If other Orbiter resources (for example, life-support consumables) could be augmented, then mission duration might be stretched to 45 days.

The PEPPO explained that it jointly managed PEP solar cell development with NASA's Lewis Research Center. Industry involvement in the PEP project was, it added, already "extensive," with several companies working on small NASA contracts or funding PEP-related work themselves. It estimated that the PEP could power a Spacelab module in Earth orbit as early as 1985 for a total development cost of only $150 million.

Spacelab 1 in Columbia's Payload Bay during STS-9 as viewed from the Flight Deck windows. Image credit: NASA

Spacelab 1 in Columbia's Payload Bay during STS-9 as viewed from the Flight Deck windows. Image credit: NASASpacelab 1, the main payload of the STS-9 Shuttle mission, reached orbit in the Payload Bay of the Orbiter Columbia on 28 November 1983. The STS-9 crew included ESA's Ulf Merbold, the first non-U.S. astronaut to reach space on board a U.S. spacecraft. Merbold was part of a six-man crew that also included Gemini, Apollo, and Shuttle veteran John Young, Skylab 3 veteran Owen Garriott, and spaceflight rookies Brewster Shaw, Robert Parker, and Byron Lichtenberg. Columbia landed at Edwards Air Force Base, California, on 8 December, ending a busy 10-day mission.

Columbia's fuel cells powered Spacelab 1, and none of the 27 Spacelab missions that followed relied on anything else. PEP work had ended in late 1981 as NASA Headquarters took charge of and terminated Shuttle augmentation and Space Station development efforts across the agency. It did this in part to clear the decks as it began formally to seek approval for a Space Station, which it billed as the "next logical step" after the Space Shuttle. President Ronald Reagan called on Congress to approve new-start funding for a Space Station during his annual State of the Union address less than two months after STS-9, in January 1984.

Sources Power Extension Package (PEP) Concept Summary, JSC-AT4-81-081, NASA Johnson Space Center, PEP Project Office, March 1981

The Solar Power Satellite Concept, NASA JSC 14898, Christopher C. Kraft; Von Karman Lecture, 15th Annual Meeting of the American Institute of Astronautics and Aeronautics, July 1979

"Spacelab joined diverse scientists and disciplines on 28 Shuttle missions," Science@NASA, 15 March 1999 -

https://science.nasa.gov/science-news/science-at-nasa/1999/msad15mar99_1/ (accessed 25 March 2017)

More Information(...)

Source:

NASA Seeks to PEP Up Shuttle/Spacelab (1981)