The Apollo Experiment That Keeps on GivingJuly 25, 2019 [NASA]

Astronaut Edwin E. Aldrin Jr. moves toward a position to deploy two components of the Early Apollo Scientific Experiments Package (EASEP) on the surface of the Moon during the Apollo 11 extravehicular activity. The Passive Seismic Experiments Package (PSEP) is in his left hand; and in his right hand is the Laser Ranging Retro-Reflector (LR3). Astronaut Neil A. Armstrong, commander, took this photograph with a 70mm lunar surface camera. Credits: NASANeil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins departed from the Moon 50 years ago, but one of the experiments they left behind continues to return fresh data to this day: arrays of prisms that reflect light back toward its source, providing plentiful insights. Along with the Apollo 11 astronauts, those of Apollo 14 and 15 left arrays behind as well: The Apollo 11 and 14 arrays have 100 quartz glass prisms (called corner cubes) each, while the array of Apollo 15 has 300.

Astronaut Edwin E. Aldrin Jr. moves toward a position to deploy two components of the Early Apollo Scientific Experiments Package (EASEP) on the surface of the Moon during the Apollo 11 extravehicular activity. The Passive Seismic Experiments Package (PSEP) is in his left hand; and in his right hand is the Laser Ranging Retro-Reflector (LR3). Astronaut Neil A. Armstrong, commander, took this photograph with a 70mm lunar surface camera. Credits: NASANeil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins departed from the Moon 50 years ago, but one of the experiments they left behind continues to return fresh data to this day: arrays of prisms that reflect light back toward its source, providing plentiful insights. Along with the Apollo 11 astronauts, those of Apollo 14 and 15 left arrays behind as well: The Apollo 11 and 14 arrays have 100 quartz glass prisms (called corner cubes) each, while the array of Apollo 15 has 300.

The longevity of the experiment can be attributed at least in part to its simplicity: The arrays themselves require no power. Four telescopes at observatories in New Mexico, France, Italy and Germany fire lasers at them, measuring the time that it takes for a laser pulse to bounce off the reflectors and return to Earth. This allows the distance to be measured to within a fraction of an inch (a few millimeters), and scientists at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory analyze the results.

The orbit, rotation and orientation of the Moon are accurately determined by lunar laser ranging. The lunar orbit and the orientation of the rotating Moon are needed by spacecraft that orbit and land on the Moon. For instance, cameras on spacecraft in lunar orbit can see the reflecting arrays, relying on them as locations accurate to less than a foot (a fraction of a meter).

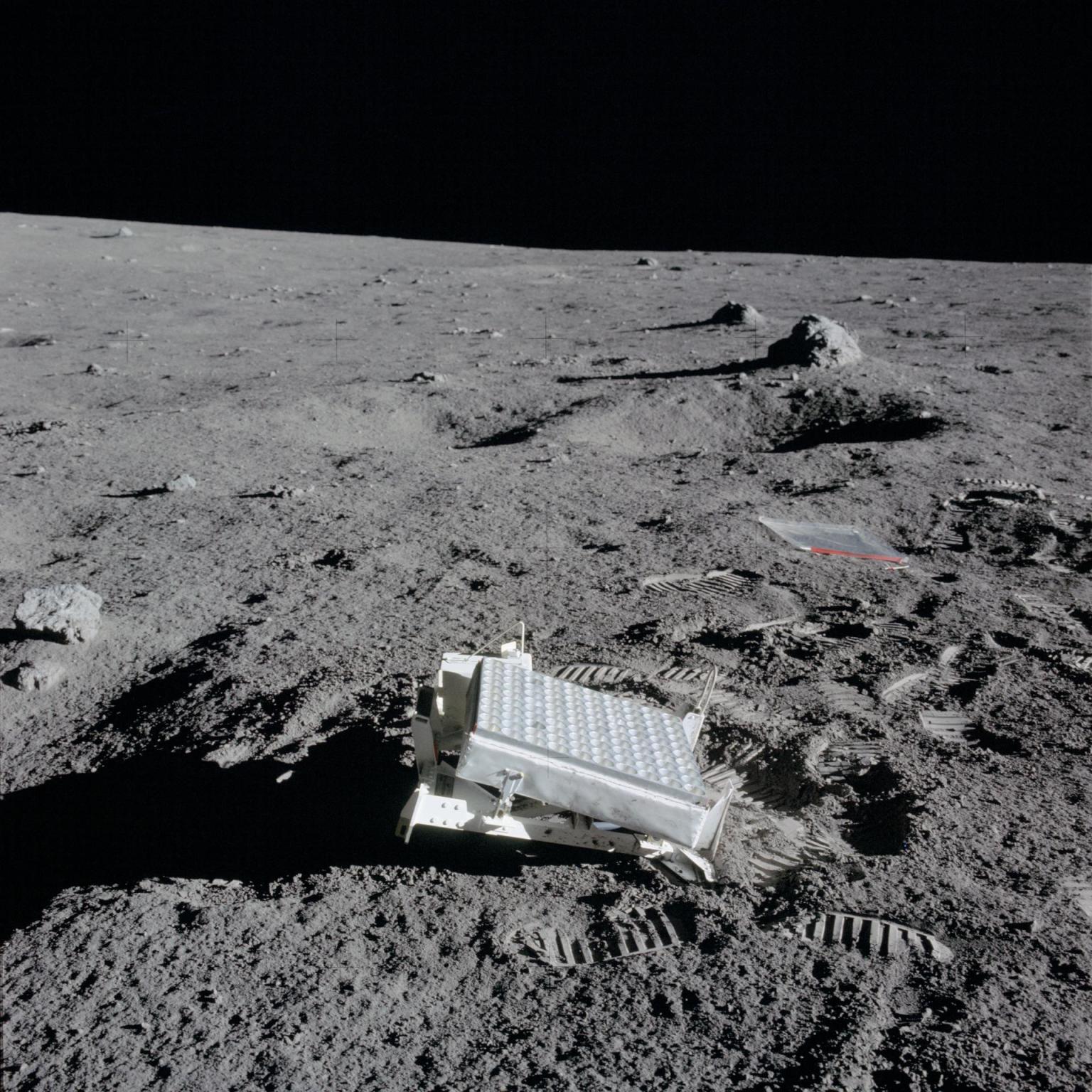

Laser ranging measurements have deepened our understanding of the dance between the Moon and Earth as well. The Moon orbits Earth at an average distance of 239,000 miles (385,000 kilometers), but lunar laser ranging has accurately shown that the distance between the two increases by 1.5 inches (3.8 centimeters) a year. A close-up view, taken on Feb. 5, 1971, of the laser ranging retro reflector (LR3), which the Apollo 14 astronauts deployed on the moon during their lunar surface extravehicular activity. Credits: NASATides in Earth's oceans are highest not when the Moon is overhead, but hours later. The highest tide is east of the Moon. There are two tidal bulges, the second one half a day later. The gravitational force between the tidal bulges and the Moon pull against and slow Earth's rotation while also pulling the Moon forward along the direction it moves in its orbit about Earth. The forward force causes the Moon to spiral away from Earth by 0.1 inches (3 millimeters) each month.

A close-up view, taken on Feb. 5, 1971, of the laser ranging retro reflector (LR3), which the Apollo 14 astronauts deployed on the moon during their lunar surface extravehicular activity. Credits: NASATides in Earth's oceans are highest not when the Moon is overhead, but hours later. The highest tide is east of the Moon. There are two tidal bulges, the second one half a day later. The gravitational force between the tidal bulges and the Moon pull against and slow Earth's rotation while also pulling the Moon forward along the direction it moves in its orbit about Earth. The forward force causes the Moon to spiral away from Earth by 0.1 inches (3 millimeters) each month.

In a similar way, Earth's gravity tugs on the Moon, causing two tidal bulges of the lunar rock. In fact, the positions of the reflecting arrays vary as much as six inches (15 centimeters) up and down each month as the Moon flexes. Measuring how much the arrays move has enabled scientists to better understand the elastic properties of the Moon (a measurement of this, called the Love number, is named after scientist A. E. H. Love).

Analysis of lunar laser data shows that the Moon has a fluid core. This was a surprise when discovered two decades ago because many scientists thought that the core would be cool and solid. The fluid core affects the directions in space of the Moon's north and south poles, which lunar laser detects.

Einstein's theory of gravity assumes that the gravitational attraction between two bodies does not depend on their composition. The Sun's gravity attracts the Moon and Earth. If this attraction depended on the composition of the two objects, it would affect the lunar orbit. Earth contains more iron than the Moon. Analysis of data from the lunar laser ranging experiment finds no difference in how gravity attracts the Moon and Earth due to their makeup.

The north star Polaris is nearly overhead at Earth's north pole. That pole changes direction compared to the stars due to the gravitational pull of the Moon and Sun on Earth's shape (the diameter at the equator is larger than the diameter at the poles). The pole will trace out a circle in the sky returning to the north star in 26,000 years. This motion of the pole is sensed and measured by lunar laser ranging.

With renewed interest in the exploration of the Moon, NASA has approved a new generation of reflectors to be placed on the lunar surface within the next decade. The improved performance of new reflectors and their wider geographical distribution on the Moon would allow improved tests of Einstein's relativity, study the deep lunar interior, investigation of the history of our celestial neighbor, and support of future exploration. The legacy of the first human visit to the Moon half a century ago will be continued.DC Agle

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

Source:

https://www.nasa.gov/feature/jpl/the-apollo-experiment-that-keeps-on-giving2 18.04.23) 2021 SIE 04 19:17 KOSMONAUTA.NET

Sięgnąć Księżyca...Pół wieku, jakie upłynęło od kiedy człowiek pierwszy raz postawił stopę na innym niż Ziemia ciele niebieskim, to w astronautyce czas wielkich wyzwań, często bezpardonowej rywalizacji, politycznych przesileń, niesamowitego postępu naukowo-technologicznego, spektakularnych sukcesów i takichże porażek.

Polecamy tekst autorstwa Pana Przemysława Rudzia z Polskiej Agencji Kosmicznej dotyczący wypraw księżycowych.

https://kosmonauta.net/2016/07/maly-krok-dla-czlowieka-ale-wielki-skok-dla-ludzkosci/