Rusty Schweickart remembers Apollo 9 (1)

By David J. Eicher | Published: Friday, March 1, 2019 [Astronomy]

The lunar module pilot relives the challenges and triumphs when humans tested their spacecraft in Earth orbit. The three Apollo 9 astronauts — left to right, Rusty Schweickart, David Scott, and Jim McDivitt — stand in front of the Apollo 9 Saturn V rocket at the historic launchpad 39A at the Kennedy Space Center in February 1969. NASABefore Neil Armstrong set foot on the Moon, becoming the first human to step on another world, we had to be ready. A big part of the readiness came earlier that year, when three astronauts flew in Earth orbit during NASA’s Apollo 9 mission. This 10-day adventure commenced March 3, 1969, less than five months ahead of the Moon landing, and it was a critical milestone. Apollo 9 marked the first complete test of the Apollo system. Commander Jim McDivitt, along with Command Module Pilot David Scott and Lunar Module Pilot Russell “Rusty” Schweickart, put all the systems through their paces.

The three Apollo 9 astronauts — left to right, Rusty Schweickart, David Scott, and Jim McDivitt — stand in front of the Apollo 9 Saturn V rocket at the historic launchpad 39A at the Kennedy Space Center in February 1969. NASABefore Neil Armstrong set foot on the Moon, becoming the first human to step on another world, we had to be ready. A big part of the readiness came earlier that year, when three astronauts flew in Earth orbit during NASA’s Apollo 9 mission. This 10-day adventure commenced March 3, 1969, less than five months ahead of the Moon landing, and it was a critical milestone. Apollo 9 marked the first complete test of the Apollo system. Commander Jim McDivitt, along with Command Module Pilot David Scott and Lunar Module Pilot Russell “Rusty” Schweickart, put all the systems through their paces.

The mission was a turning point for several reasons. It was the first live orbital test of the lunar module (LM), the lander that would carry two astronauts to the Moon’s surface. The rendezvous and docking procedures between the LM and the command/service module were also tested. And it offered practice runs for astronauts to walk in space in order to conduct maintenance and fix problems that could arise far from home.

Apollo 10 would perform a full test run, circling the Moon, detaching the LM, doing practically everything except for the landing itself. That occurred in May 1969, with a crew of Tom Stafford, John Young, and Gene Cernan. But without the milepost of Apollo 9, the venture would have stopped and rebooted.

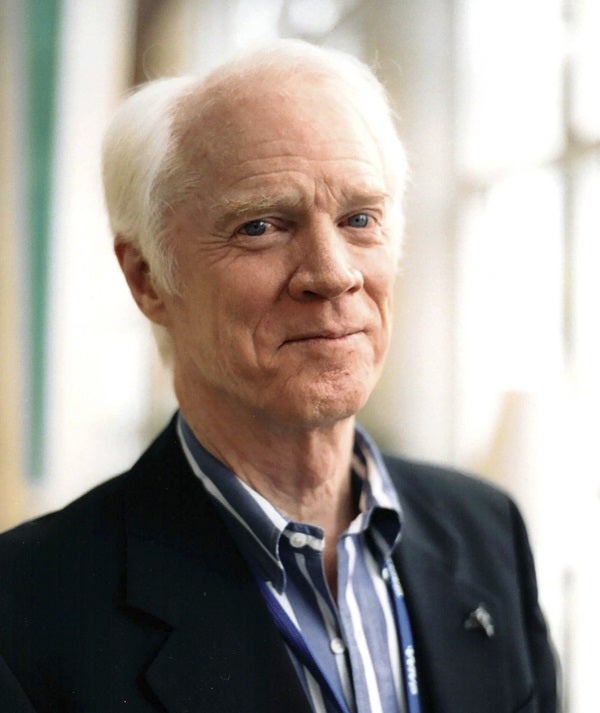

I interviewed Schweickart, now 83 and as razor sharp as ever, about his legendary Apollo 9 experience. Today, Schweickart is as active as ever. B612 FoundationQ: With Apollo, there were some crew reassignments. When things finally settled and you prepared for Apollo 9, what sticks out in your memories about that time?A: Jim McDivitt and I spent day after day, night after night, week after week up at Grumman as Lunar Module 2, LM-2, was coming down the production line. LM-2 was going to be the first flight vehicle. I cannot tell you the agony of Jim and I in that cockpit in the middle of the night, testing things along with the team.

Today, Schweickart is as active as ever. B612 FoundationQ: With Apollo, there were some crew reassignments. When things finally settled and you prepared for Apollo 9, what sticks out in your memories about that time?A: Jim McDivitt and I spent day after day, night after night, week after week up at Grumman as Lunar Module 2, LM-2, was coming down the production line. LM-2 was going to be the first flight vehicle. I cannot tell you the agony of Jim and I in that cockpit in the middle of the night, testing things along with the team.

Jim and I kept looking over at one another and shaking our heads. We would work with the engineers and go over the wiring diagrams, and try to puzzle out what had happened, why it did that, why it didn’t do what it was supposed to do, and so on. That happened continually.

At one point, Jim and I finally looked at each other, we shook our heads, and I don’t know whether it was Jim or me, but we looked and said, “Are we really going to fly this thing? Is this something we should fly? Even if we can sweat blood and tears, and get it to the end of the testing cycle, is this the right thing to do?”

That was when we slipped from LM-2 to LM-3. Of course, part of the deal was that, even before the decision was made, I think, Grumman was pushed into redoing the testing team and separating it from the design team. Q: But you overcame the dilemmas and began training.A: Yes, and with Apollo, we had the big mission simulators, which were not just complex pieces of gear. From the inside, they looked like and operated like the spacecraft. But when you looked out the window, there was this humongous optical system. The simulator itself was in the middle of this monstrous optical system which, when you looked out the window, gave you a virtual image.

But testing in the suit was rough and exhausting. You would come out of a couple hours in the simulator or neutral buoyancy testing, the underwater testing, just beat. You’re wearing a suit, and you’ve got weights all over it. You’re going upside down and sideways. You get to do a lot of that simulation and training, and you come out of the suit, and you’ve got blood running down your shoulders.

It digs into you. You’ve got your whole weight into it sometimes. You’re lying on your side, and your arm is hard as a rock because you’re pressurized with 3.5 psi. There were many, many days when, if you didn’t actually have blood running down you when you got the suit off, you had bruises all over your body. A nighttime view of launchpad 39A shows the Apollo 9 Saturn V rocket and capsule ready for countdown during preparations for the 10-day mission. NASAQ: When the mission approached, what was it like to ready yourself and then launch in a Saturn V rocket? A: Even several months before the spacecraft is at the pad, the whole spacecraft gets stacked and put together, and connected electrically. So, you begin doing some of the final testing on the vehicle itself when it’s stacked on the launchpad. Now, you’re no longer in the Rockwell factory or the Grumman factory, the factory floor and people walking all around. You’re now on the launchpad, on top of that big Saturn V, 360-some feet in the air, and the gantry all around.

A nighttime view of launchpad 39A shows the Apollo 9 Saturn V rocket and capsule ready for countdown during preparations for the 10-day mission. NASAQ: When the mission approached, what was it like to ready yourself and then launch in a Saturn V rocket? A: Even several months before the spacecraft is at the pad, the whole spacecraft gets stacked and put together, and connected electrically. So, you begin doing some of the final testing on the vehicle itself when it’s stacked on the launchpad. Now, you’re no longer in the Rockwell factory or the Grumman factory, the factory floor and people walking all around. You’re now on the launchpad, on top of that big Saturn V, 360-some feet in the air, and the gantry all around.

You take a break for lunch, and all of the guys in the control room have taken a break for lunch, and you’ve got a brown bag there with your sandwiches and your drink. Regularly, along with everybody on a crew, you would walk out along the steel structure of the gantry up at that 360-foot level and sit out dangling your legs over the ocean, looking out over the ocean, the highest thing in Florida, in more ways than one, probably. Those kinds of moments are the things that are so personal and stay with you. They’re just wonderful moments.

The celebrated Günter Wendt was one of the old Peenemünde guys. He had sort of average height but was a very thin guy. He had a wonderful German accent, you know. He had this terrific sense of humor. He knew all of the guys very personally. He was the guy who put every astronaut in the spacecraft, from Mercury through Gemini and well into, if not all the way through, Apollo. He literally was your friend in terms of the last guy who patted you on the shoulder, and gave you a thumbs-up and said, “Go vor it!” in a German accent.

Then you get strapped in, and it gets serious. Let me tell you another interesting and very personal part of it. One of the things, of course, when you get strapped into the spacecraft and ready to launch, is that something might go wrong, and you’ve got the world’s biggest firecracker 300 feet under you. If there’s a problem, you need to get your butts out of there fast and get over to the slidewires and into the little dolly, and jump in and cut it loose, and slide to safety, right? That’s a big deal.

Yet, when you’re lying there side by side, ready to launch in Apollo, and especially with the slight amount of pressure in the suit — they’re not fully pressurized, but they’re pretty bulky and a little bit of overpressure — you can’t lay side by side with your arms down at your side. It’s not wide enough. So, with Dave sitting in the middle and McDivitt on the left and me on the right, either Dave’s arm was over mine or mine was over his, and the same with Jim on the other side. So, you had to take turns with whose arm was going to be on top, especially if you were strapped in tight because you couldn’t shift sideways as you could during training.

So, Günter tightened us in. Of course, the last thing Günter does is put an extra pull on the straps to tighten you in before he pats you on the shoulder and says goodbye. Then he closed the hatch. Dave and I waited until the hatch was closed, and then we both reached up, and we loosened our shoulder straps a little bit. We did that, of course, because in an emergency it would make a real difference. The Mission Operations Control Room — in Building 30 of what came to be called the Johnson Space Center in Houston — was a beehive of activity during Apollo 9. NASAThen we launched that way. No big deal — we weren’t thinking anything about it. We get up to the end of first-stage burn. Of course, picture yourself doing that two and a half minutes or so into flight, the first stage is going to burn out. You started out at 1.1g or something like that at liftoff, but burning 6 million pounds of fuel. By the time you’re up there, you’re at 6.5g.

The Mission Operations Control Room — in Building 30 of what came to be called the Johnson Space Center in Houston — was a beehive of activity during Apollo 9. NASAThen we launched that way. No big deal — we weren’t thinking anything about it. We get up to the end of first-stage burn. Of course, picture yourself doing that two and a half minutes or so into flight, the first stage is going to burn out. You started out at 1.1g or something like that at liftoff, but burning 6 million pounds of fuel. By the time you’re up there, you’re at 6.5g.

If you’ve got those five big engines at the bottom end of this now-hollow tin can pushing up with 7.5 million pounds of force, that tin can is compressed. When those five engines shut off suddenly, that tin can expands. It gets something like 6 inches longer, quickly. When it did that, it kicked us in the back. Dave Scott and I went flying toward the instrument panel, and both of us stopped with our helmets and visors about an inch away from it.

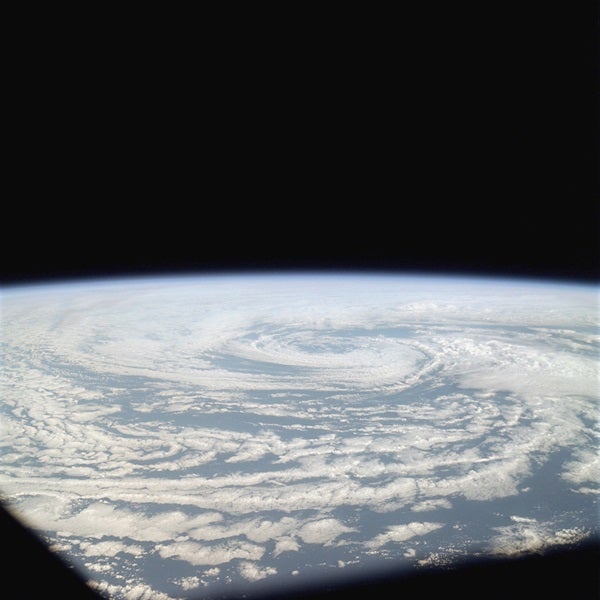

We looked at each other and it was like, “Whoa man, was that close!” So, that was one of the things we briefed the next crew on before their launch. Don’t loosen your shoulder straps, buddies. The astronauts imaged a huge cyclonic storm system some 1,200 miles north of Hawaii. NASAQ: And then what do you feel as you move skyward?A: Very slowly, you go up, and after 10 seconds or so, you’re past the top of the gantry. Now you’re 300 feet above the ground right there. That blastoff sound has to go down 300 feet and then back up 300 feet because the sound you’re hearing is not coming up through the structure, it’s coming through the air. Very, very rapidly, after 10, 15, 20 seconds, you can no longer hear the engines.

The astronauts imaged a huge cyclonic storm system some 1,200 miles north of Hawaii. NASAQ: And then what do you feel as you move skyward?A: Very slowly, you go up, and after 10 seconds or so, you’re past the top of the gantry. Now you’re 300 feet above the ground right there. That blastoff sound has to go down 300 feet and then back up 300 feet because the sound you’re hearing is not coming up through the structure, it’s coming through the air. Very, very rapidly, after 10, 15, 20 seconds, you can no longer hear the engines.

You can still feel them. What do you really feel? You’ve been in a train and probably in a sleeper in a train. You’re going down the tracks fairly fast and occasionally you get this sideways motion as the tracks aren’t exactly lined up. It’s a very solid and somewhat even gentle, rounded kind of sideways acceleration.

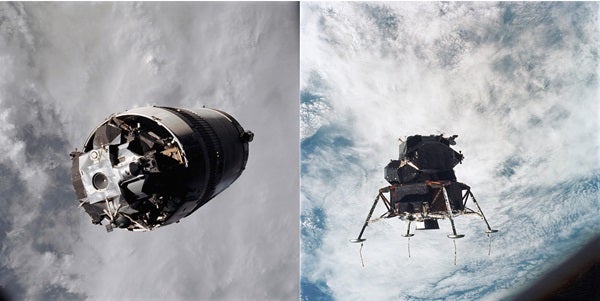

With those engines going back and forth, it’s like balancing a broomstick on your finger: You’re moving your finger back and forth, left and right, in and out, to keep the broomstick straight up. Those engines are doing exactly that with you. So, you’re feeling this almost like a train, this very solid, sideways, small oscillations and things.Q: Apollo 9 was critical in docking and redocking the LM with the command module. Did you have a lot of confidence in performing the docking maneuvers that were required for the mission?A: Yeah. There’s a little bit of yes and no, but for the most part yes, in the sense of the simulators were pretty good. If you’re looking at it from the standpoint of the command module docking with the lunar module, you’re sitting there like you’re in a chair, and you’ve got a controller on each side, a very controllable spacecraft. You’re moving in and lying face up. It’s like pulling into your garage with your car. Easier in some ways, almost. It’s not just right and left, but it’s up and down, so there’s a little bit of that; you’re adding a dimension to it. But it’s pretty damn straightforward. Left: In Earth orbit, the LM Spider appears to remain attached to the Saturn V third stage, as photographed from the command/service module March 3, 1969. Right: Spider hovers above Earth in lunar landing configuration. NASAThe thing which was the most attention-getting in terms of the docking and transferring between the two vehicles was the fact that you are going through a tunnel. Unlike the docking mechanism that exists now and has existed ever since Apollo, where the docking mechanism is on the periphery of the cylindrical tunnel, in the command module in the Apollo program, the docking mechanism was in the middle of the tunnel. It was a probe which was a Rube Goldberg device cube sitting in the middle of the command module tunnel, and you stuck the tip of that probe into a funnel, which was the drogue, which was mounted at the top of the tunnel in the lunar module.

Left: In Earth orbit, the LM Spider appears to remain attached to the Saturn V third stage, as photographed from the command/service module March 3, 1969. Right: Spider hovers above Earth in lunar landing configuration. NASAThe thing which was the most attention-getting in terms of the docking and transferring between the two vehicles was the fact that you are going through a tunnel. Unlike the docking mechanism that exists now and has existed ever since Apollo, where the docking mechanism is on the periphery of the cylindrical tunnel, in the command module in the Apollo program, the docking mechanism was in the middle of the tunnel. It was a probe which was a Rube Goldberg device cube sitting in the middle of the command module tunnel, and you stuck the tip of that probe into a funnel, which was the drogue, which was mounted at the top of the tunnel in the lunar module.

So when McDivitt and I went 100 miles away from the command module to test all the engines and the rendezvous procedure that would be used coming up off the Moon, the big question was, “OK, when we get back, are we going to be able to get through the tunnel?” You not only had to dock, but you had to get all that crap out of the middle of the tunnel if you were going to get back to your heat shield. Q: Can you talk a bit about your spacewalk, and what it was like psychologically to be out there? You had the first self-contained life support system with your suit. What was it like floating? What was it like looking down on Earth?A: That was the lowest and the highest point in my life. I barfed on the third day of the mission, which was the first day we got in the lunar module. I was the lunar module pilot, and I had to test the lunar module. We thought seriously that we may have to cancel the mission — not just that it was uncomfortable, but we talked very seriously about canceling the mission. We did cancel the extravehicular activity, the spacewalk, and it was a very serious question, whether if we had to cancel the mission because yours truly was sick. We were going to miss John Kennedy’s commitment to go to the Moon and return a man by the end of the decade.