'Working a Monkey Board': The First 50 Years of Spacewalking (Part 1)By Ben Evans, on March 18th, 2015

Five decades have now passed since humanity’s first foray beyond the confines of their pressurized spacecraft and into the airless void beyond. Photo Credit: NASA

Five decades have now passed since humanity’s first foray beyond the confines of their pressurized spacecraft and into the airless void beyond. Photo Credit: NASAFifty years ago, today, on 18 March 1965, a 30-year-old Soviet cosmonaut named Alexei Leonov became the first human in history to depart the confines of his spacecraft in a pressurized suit and float freely into the limitless void beyond. (...) Leonov spent 12 minutes outside the Voskhod 2 spacecraft, tumbling in the void, as part of the latest in a line of Soviet spectaculars, designed to outdo the United States. It had long been apparent that spacewalking, or “Extravehicular Activity” (EVA), was a central tenet of Project Gemini that NASA needed to master, before sending humans to the Moon in fulfilment of President John F. Kennedy’s bold challenge. The first U.S. spacewalk, by astronaut Ed White, occurred a few weeks later, in June 1965, and ushered in a new technology which would see humans explore the surface of the Moon, weld, repair, and upgrade satellites and space telescopes, work in untethered conditions, and build one of the brightest objects in Earth’s skies: the International Space Station (ISS). (...)

By this stage, Gemini IV’s official press kit had made reference to a “possible extravehicular activity,” which became a certainty just a few days later. Nor would Ed White merely stand on his seat and poke his head through the upper hatch; he would actually leave the spacecraft and maneuver around with the aid of his hand-held device. Following their launch on 3 June, White ventured outside the spacecraft for 21 minutes and “walked” across part of the world, starting over the central Pacific, over California and later Texas, and eventually reaching southern Florida and the island chains of Cuba and Puerto Rico. From inside Gemini IV, McDivitt was concerned that his photography of the event was “not very good,” but in reality his images of America’s first spacewalker proved an iconic record of the early annals of space exploration.

The first few piloted Gemini missions had been assigned very specific tasks—an inaugural shakedown of the vehicle on Gemini 3, the EVA on Gemini IV, long-duration and fuel cells on Gemini V, rendezvous on Gemini VI, and long-duration on Gemini VII—but each of the final six flights of the program were expected to feature a spacewalk of significantly greater complexity than had been performed by White. (...)

https://www.americaspace.com/2015/03/18/working-a-monkey-board-the-first-50-years-of-spacewalking-part-1/Walking on an Alien World: The First 50 Years of Spacewalking (Part 2)By Ben Evans, on March 19th, 2015

A mere four years after humanity’s first spacewalk, EVA and space suit technology advanced sufficiently to permit Neil Armstrong’s historic first steps on the Moon. Photo Credit: NASA

A mere four years after humanity’s first spacewalk, EVA and space suit technology advanced sufficiently to permit Neil Armstrong’s historic first steps on the Moon. Photo Credit: NASA(...) Performing EVA on another celestial body, they found that the most natural gait was a loping motion, in which they alternated feet, pushed off with each step, and floated ahead, then planted the other foot. Other techniques included “skipping strides” and “kangaroo hops,” necessitated by the peculiar one-sixth terrestrial gravity. They had to take care when turning and stopping. “I noticed immediately that my inertia seemed much greater,” Aldrin wrote in his memoir,

Men from Earth. “Earthbound, I would have stopped my run in just one step … an abrupt halt. I immediately sensed that if I tried this on the Moon, I’d be face-down in the lunar dust. I had to use two or three steps to sort of wind down. The same applied to turning around. On Earth, it’s simple, but on the Moon, it’s done in stages.” In total, Armstrong spent two hours and 14 minutes on the surface; Aldrin a little less, at one hour and 46 minutes. (...)

https://www.americaspace.com/2015/03/19/walking-on-an-alien-world-the-first-50-years-of-spacewalking-part-2/Operational EVAs: The First 50 Years of Spacewalking (Part 3)By Ben Evans, on March 21st, 2015

The final Skylab mission marked the first occasion on which a spacewalk was conducted on Christmas Day. Photo Credit: NASA

The final Skylab mission marked the first occasion on which a spacewalk was conducted on Christmas Day. Photo Credit: NASA(...) “The spacewalks are just absolutely the high point,” Lousma explained to the NASA oral historian, years later. “It really is the most memorable part of being in orbit; just an unusual experience, in that when you go outside, it’s different than being inside. When you’re inside, you look through the window and you see part of world.” Outside, in the ethereal void, the Earth was an enormous “sphere,” just beyond the helmet visor. Lousma was dazzled by the glare of the unfiltered sunlight and was astonished that, for the very first time, he really felt the sensation of speed and motion over Earth. At the same time, however, unlike the related sensations associated with speed in an aircraft, there was no vibration and absolutely no sound. “It’s like gliding along on this magic carpet,” he said, “going into the sunset and sunrise every hour and a half … doing that for six hours.” On one occasion, perched on the end of the ATM, installing a film cassette, Lousma remembered moving into orbital night, somewhere over Siberia, he guessed, and being thrown headlong into blackness. Through his visor, he could hardly see his own gloved hands and had the profound realisation that “it’s just me, God, the spacecraft and my buddies and that’s it!” (...)

https://www.americaspace.com/2015/03/21/spacewalking-from-space-stations-the-first-50-years-of-spacewalking-part-3/Repair and Salvage: The First 50 Years of Spacewalking (Part 4)By Ben Evans, on March 22nd, 2015

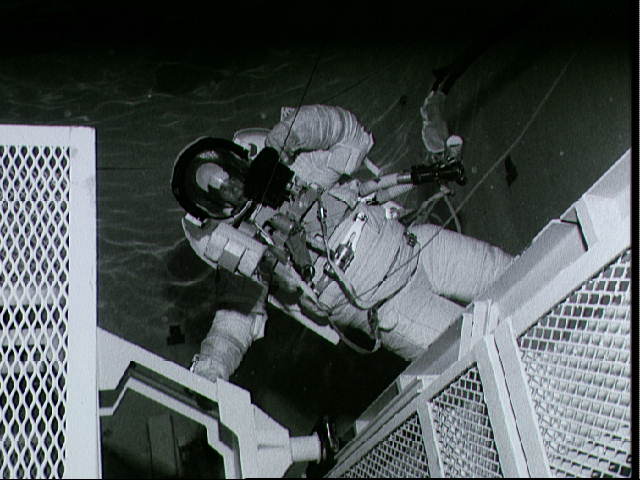

Originally, the shuttle was intended never to require an EVA capability. In the 1970s, it was regarded as the spacegoing equivalent of a commercial airliner … but when it became clear that problems might be experiencing closing the payload bay doors and attending to other technical issues, an EVA capability evolved. Many of the techniques for attending to contingencies would have been trialed by Lenoir and Allen on STS-5. Photo Credit: NASA

Originally, the shuttle was intended never to require an EVA capability. In the 1970s, it was regarded as the spacegoing equivalent of a commercial airliner … but when it became clear that problems might be experiencing closing the payload bay doors and attending to other technical issues, an EVA capability evolved. Many of the techniques for attending to contingencies would have been trialed by Lenoir and Allen on STS-5. Photo Credit: NASA(...) In December 1982, NASA announced that the EVA would be attempted by astronauts Story Musgrave and Don Peterson on STS-6, the maiden voyage of Shuttle Challenger, which eventually launched in April 1983. “It didn’t give us much time to train,” Peterson recalled in his NASA oral history. “I didn’t have much experience in the suit, but the advantage we had was that Story was the astronaut office’s point of contact for the suit development, so he knew everything there was to know. He’d spent 400 hours in the water tank, so he didn’t really have to be trained!” By his own admission, Peterson’s EVA training for STS-6 “was pretty rushed.” He recalled being underwater in the Weightless Environment Training Facility (WET-F) at the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas, on 15-20 occasions, “and that’s not really enough to know everything you need to know.” (...)

https://www.americaspace.com/2015/03/22/repair-and-salvage-the-first-50-years-of-spacewalking-part-4/Ready for Space Station Building: The First 50 Years of Spacewalking (Part 5)By Ben Evans, on March 28th, 2015

Story Musgrave works at the end of Endeavour’s mechanical arm during activities to service the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) in December 1993. Photo Credit: NASA

Story Musgrave works at the end of Endeavour’s mechanical arm during activities to service the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) in December 1993. Photo Credit: NASA(...) The four STS-49 EVAs totaled 25 hours and 27 minutes, longer than had been accomplished on any prior shuttle mission, and required some sporty additions to the astronauts’ pure-white suits for identification. Thuot (EV1) wore red stripes, Hieb (EV2) had no stripes, Thornton (EV3) had dashed stripes and Akers (EV4) had red diagonal hatches. It was a system which would be followed on several other shuttle missions involving more than two spacewalkers, throughout the 1990s and into the present century, most recently on STS-134, the final flight of Endeavour, in May-June 2011.

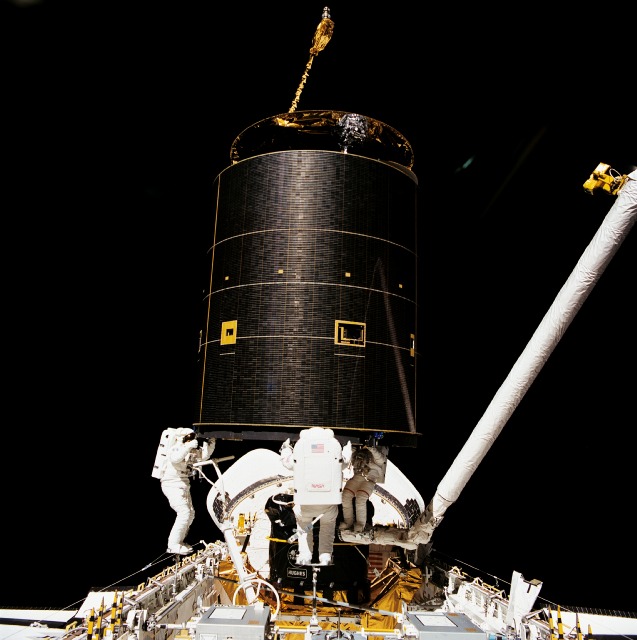

In the first, and so far only, three-person EVA, astronauts Rick Hieb, Tom Akers and Pierre Thuot manhandle Intelsat 603 into Endeavour’s payload bay for the attachment of a new rocket motor. Photo Credit: NASA

In the first, and so far only, three-person EVA, astronauts Rick Hieb, Tom Akers and Pierre Thuot manhandle Intelsat 603 into Endeavour’s payload bay for the attachment of a new rocket motor. Photo Credit: NASASTS-49 demonstrated that more EVA expertise was acutely needed before the construction of Space Station Freedom could begin. “We need better ways to train so that the learning curve isn’t quite so steep,” said the mission’s commander, Dan Brandenstein, whilst Pierre Thuot added that the Intelsat 603 retrieval task was something that the crew “couldn’t train for fully”. As a result, in November 1992, NASA announced that a future shuttle flight, STS-54, would feature an EVA to “fine-tune the methods of training astronauts for assembly tasks in space” and “increase the spacewalk experience levels of astronauts, ground controllers and instructors”. It was noted that more EVA flights would be manifested, but that they would only be attempted if they did not impact primary mission objectives.

https://www.americaspace.com/2015/03/28/ready-for-space-station-building-the-first-50-years-of-spacewalking-part-5/Traversing the New Frontier: The First 50 Years of Spacewalking (Part 6)By Ben Evans, on March 29th, 2015

Terry Virts is pictured working on cable-routing activities in support of the future International Docking Adapters (IDAs) during EVA-29 on 21 February 2015. This was the first spacewalk in the 50th anniversary year since Alexei Leonov’s pioneering EVA. Photo Credit: NASA

Terry Virts is pictured working on cable-routing activities in support of the future International Docking Adapters (IDAs) during EVA-29 on 21 February 2015. This was the first spacewalk in the 50th anniversary year since Alexei Leonov’s pioneering EVA. Photo Credit: NASALess than a month ago, on 1 March 2015, U.S. astronauts Barry “Butch” Wilmore and Terry Virts concluded a spectacular series of three EVAs to prepare the International Space Station (ISS) for its most significant phase of expansion and relocation of hardware since the end of the shuttle era. They laid 340 feet (103 meters) of cables in support of the arrival of two International Docking Adapters (IDAs)—critical for NASA’s future Commercial Crew aspirations—as well as a further 400 feet (122 meters) of cables for the Common Communications for Visiting Vehicles (C2V2) architecture and prepared two berthing ports on the Tranquility node for use later in 2015. In concluding the last of these EVAs, Wilmore and Virts completed the 187th spacewalk performed by astronauts and cosmonauts from the United States, Russia, Canada, France, Japan, Germany, Sweden, and Italy since December 1998 to assemble and maintain the largest and most complex engineering achievement in human history. It is a mammoth effort which is expected to continue this year and throughout the station’s operational lifetime. (...)

In December 1988, Frenchman Jean-Loup Chrétien became the first non-Russian and non-U.S. citizen in history to embark on an EVA. One of the tasks of Chrétien and his Soviet crewmate, cosmonaut Aleksandr Volkov, was the installation of the French ERA experiment on Mir’s exterior, as part of demonstrations of the construction of rigid structures in microgravity. “You forget about your space suit very quickly,” Chrétien recalled later, “so you’re really in the impression that you are free floating with nothing … just swimming. It was fascinating.” Orbital darkness did not bother him: the lights on his helmet and Earth’s natural albedo provided an eerie illumination of their own. Aged 50, the Frenchman also secured a record as the world’s oldest spacewalker, an accolade he would hold until 1993. (...)

Later in 1990, another EVA became necessary, not because of an issue pertaining to Mir, but to the Soyuz TM-9 spacecraft of cosmonauts Anatoli Solovyov and Aleksandr Balandin. Following their launch in February, it became clear that three of their descent module’s eight thermal insulation blankets had become detached, threatening to obstruct critical sensors during re-entry. In July, the cosmonauts performed a spacewalk, during which they successfully tended to the blankets, but inadvertently violated an EVA egress procedure from the Kvant-2 module airlock, which damaged the hinges around the circumference of the hatch. The error became evident when Solovyov and Balandin came to return inside Mir, and the hatch refused to close properly, forcing them to leave it slightly ajar and use Kvant-2’s inner compartment as a contingency airlock. By the time they returned inside the station, the cosmonauts had spent seven hours and 16 minutes in vacuum, a new Soviet EVA record. (...)

Finally, on 1 October,

during the STS-86 mission to Mir, U.S. astronaut Scott Parazynski and Russian cosmonaut Vladimir Titov performed a spacewalk outside shuttle Atlantis. This marked the first occasion that a Russian had spacewalked outside a non-Russian spacecraft, wearing a non-Russian suit, as well as making Titov the first non-U.S. shuttle spacewalker. Eight weeks later, on STS-87, Japanese astronaut Takao Doi became the second, and by the end of the 30-year shuttle era in July 2011 spacewalkers from Switzerland, Canada, France, Germany, and Sweden had done likewise. Notably, in December 1999, Swiss astronaut Claude Nicollier became the European Space Agency (ESA) spacefarer to perform an EVA from the shuttle, during the STS-103 Hubble Space Telescope (HST) servicing mission. (...)

Jerry Ross, pictured during STS-88, the first shuttle mission of the International Space Station (ISS) era. Photo Credit: NASA

Jerry Ross, pictured during STS-88, the first shuttle mission of the International Space Station (ISS) era. Photo Credit: NASADespite the steady expansion of spacewalking to other nations, until relatively recently only the United States and Russia carried the capability to conduct EVA.

That monopoly ended in September 2008, when Chinese crew member Zhai Zhigang performed a 22-minute spacewalk outside his Shenzhou 7 spacecraft. His comrade, Liu Boming, also embarked on a Stand-Up EVA (SEVA) to hand him a Chinese flag. Although China has yet to perform a second EVA, the achievement made the world’s most populous nation the third to demonstrate a home-grown capability to execute spacewalks in its own suits, with its own citizens and from its own spacecraft. (...)

Age has also proven little of a barrier for spacewalkers, with Russian cosmonaut Pavel Vinogradov the current record-holder for the upper limit, having performed an EVA in April 2013, aged 59. In doing so, he eclipsed the previous record-holder, U.S. astronaut Story Musgrave, who had been 58 years old when he led the spacewalks which serviced the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) in December 1993. The oldest female spacewalker was Linda Godwin, who was 49 years old at the time of her final career EVA on STS-108 in December 2001. At the lower limit, Alexei Leonov himself was just 30 years old at the time of his pioneering EVA and consequently holds the record for the world’s youngest spacewalker. And the youngest female spacewalker was America’s first woman to walk in space, Kathy Sullivan, who turned 33 just two days before launching aboard Challenger on Mission 41G in October 1984. (...)

https://www.americaspace.com/2015/03/29/traversing-the-new-frontier-the-first-50-years-of-spacewalking-part-6/2) 31 lat temu, 13.05.1992 astronauci P. J. Thuot (USA), R. J. Hieb (USA) i T. D. Akers (USA) wykonali pierwszy i do tej pory jedyny spacer kosmiczny z udziałem 3. astronautów.

https://twitter.com/ShuttleAlmanac/status/1657170963849682944