Lot, który mógl zakończyć się katastrofą.

Pierwszy nocny start i lądowanie w programie STS.

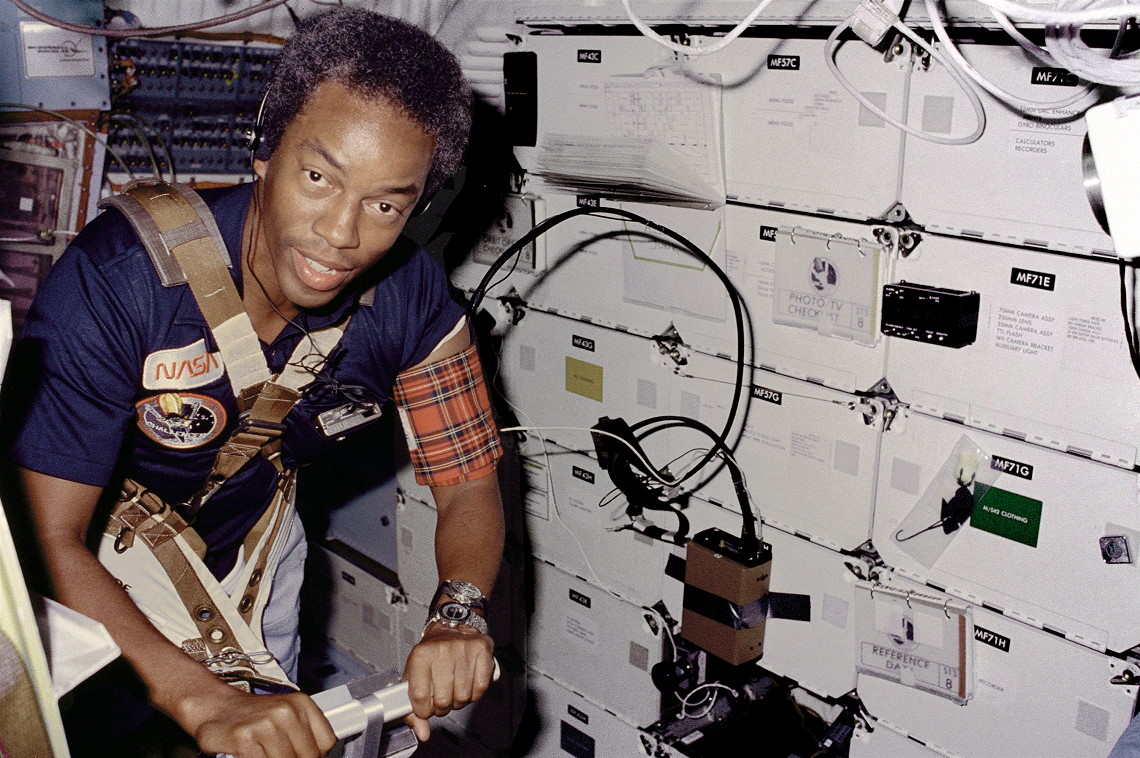

Pierwszy lot czarnoskórego astronauty w programie STS.

Drugi lot , w którym wzięli udział astronauci z naboru z roku 1978.

Dowódca załogi Richard Truly został później administratorem NASA , a pilot Daniel Brandenstein dowodził pierwszym lotem ostatniego wprowadzonego do służby wahadłowca Endeavour.

Początkowo załoga miała liczyć cztery osoby.

Nastąpiła częściowa wymiana ładunku z powodu problemów z TDRS podczas misji STS-6.

Pojawiły się 33 anomalie podczas misji. Naliczono 7 poważnych uszkodzeń osłony cieplnej i 49 niewielkich , co w porównaniu z innymi lotami nie było dużą liczbą.

A total of thirty-three in-flight anomalies were eventually reported. As well as the issues above, STS-8's more minor problems ranged from faulty thermostats to an unusually high amount of dust in the cabin.Załoga była nieświadoma, że w pierwszej fazie lotu, po starcie groziła jej awaria mogąca mieć katastrofalne skutki. Po wyłowieniu z wody pomocniczych rakiet na paliwo stałe oraz przetransportowaniu ich do bazy NASA okazało się, że doszło do awarii prawej rakiety, w której ochrona żaroodporna stalowej dyszy silnika została prawie na wylot przepalona. Z zewnętrznej strony jest ona chroniona przed gorącymi spalinami przez warstwę ablacyjną o grubości 7,5 cm. Podczas dwóch minut pracy silnika część warstwy wyparowuje, a jej grubość zmniejsza się o około połowę. Przy starcie STS-8 warstwa ochronna zbyt szybko wyparowała – pozostało 5 mm, co mogło doprowadzić do przepalenia dyszy. Efektem byłoby zmniejszenie ciągu silnika, zboczenie promu z kursu, a następnie destrukcja. Za przyczynę awarii uznano nieodpowiednią żywicę użytą do produkcji warstwy ablacyjnej w silnikach SRB. Wobec tej awarii wstrzymano następny lot wahadłowca planowany na 30 września 1983 roku. Następnie przesunięto raz jeszcze o miesiąc, aby znaleźć przyczynę awarii i sprawdzić czy przy kolejnych egzemplarzach rakiet nie powtórzy się podobna sytuacja. Pomyślne badania pozwoliły na następny start w dniu 28 listopada 1983 roku.https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/STS-8https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/STS-8http://www.spacefacts.de/english/bio_ast.htm

30 Years Ago: First Shuttle Night Launch, First African-American Astronaut, Oldest Man in Space (Part 1)

30 Years Ago: First Shuttle Night Launch, First African-American Astronaut, Oldest Man in Space (Part 1)By Ben Evans, on August 31st, 2013

(...) This nocturnal launch had been simulated on the ground. “We concentrated on flying night launches and night landings in a darkened simulator,” Bluford recalled. “We learned to set our light levels low enough in the cockpit that we could maintain our night vision, and I had a special lamp mounted on the back of my seat so that I could read the checklist in the dark. The only thing that wasn’t simulated was the lighting associated with the Solid Rocket Booster ignition and the firing of the pyros for SRB and External Tank separation.” (...)

https://www.americaspace.com/2013/08/31/30-years-ago-first-shuttle-night-launch-first-african-american-astronaut-oldest-man-in-space-part-1/30 Years Ago: First Shuttle Night Launch, First African-American Astronaut, Oldest Man in Space (Part 2)By Ben Evans, on September 1st, 2013

Photo Credit: NASA

Photo Credit: NASA(...) With the Insat-1B deployment behind them, the crew set to work on their next major objective: testing the muscle of their ship’s mechanical arm with the Payload Flight Test Article (PFTA). Although it would not be released into space, this giant dumbbell was the largest payload yet manipulated by the RMS. Yet even the PFTA was barely a third of the weight of the enormous Long Duration Exposure Facility, destined to be placed into orbit by another shuttle crew in the spring of 1984. Nonetheless, its forward and aft screens closely mimicked the visibility and maneuverability obstacles that future astronauts deploying large, cylindrical structures might face. In particular, PFTA became the first shuttle-borne cargo with a “five point” attachment to the payload bay—a keel and four longeron fittings—all of which were out of the direct view of the crew.

The dumbbell-shaped Payload Flight Test Article (PFTA) was designed to test the maneuverability and capabilities of the shuttle’s Remote Manipulator System (RMS) arm. Photo Credit: NASA

The dumbbell-shaped Payload Flight Test Article (PFTA) was designed to test the maneuverability and capabilities of the shuttle’s Remote Manipulator System (RMS) arm. Photo Credit: NASAAs a result, Gardner and Bluford relied totally upon cameras fitted to the RMS. With Gardner at the controls, the dumbbell was first grappled by one of its two “active” fixtures and subjected to a variety of tests, as Truly pulsed Challenger’s thrusters. These tasks helped to satisfy a number of test objectives to verify ground-based simulations, assess visual cues for payload handling, and demonstrate both hardware and computer software. During each activity, the RMS was employed in both manual and automatic modes. The two grapple fixtures on the payload provided different geometries and mass properties for the arm. Much of the payload’s mass was situated at its aft end, thanks to a quantity of lead ballast, and Gardner’s evaluations helped to verify that the RMS could position a large structure within 1.9 inches and one degree of accuracy in respect to the shuttle’s axes. (...)

https://www.americaspace.com/2013/09/01/30-years-ago-first-shuttle-night-launch-first-african-american-astronaut-oldest-man-in-space-part-2/STS-8: The First Shuttle Night Launch & LandingAug. 30, 2018

With its first two flights successfully completed, Space Shuttle Challenger was ready to head back into space. As with its previous flights, this one would also be known for several “firsts.” The primary objective of Challenger’s third mission, STS-8, was to deploy the Insat-1B weather and communications satellite for India. The final orbital location of Insat-1B dictated that Challenger launch and land at night, the first time in the Shuttle program. STS-8 was originally planned to fly the second Tracking and Data Relay Satellite (TDRS) to expand space-to-ground communications between Mission Control and orbiting Space Shuttles, but during the launch of the first TDRS on STS-6, its Inertial Upper Stage (IUS) placed it into a stable but incorrect orbit. NASA managers decided to replace the TDRS on STS-8 until the IUS problem could be identified and corrected. Replacing TDRS was the Canadian-built Remote Manipulator System (RMS), or robot arm, and the Payload Flight Test Article (PFTA), an 8,500–pound dumbbell-shaped structure designed to evaluate the dynamics of the RMS.

NASA announced the crew for STS-8 in April 1982– Commander Richard H. Truly, a veteran of the STS-2 mission, and three first time flyers, Pilot Daniel C. Brandenstein and Mission Specialists Dale A. Gardner and Guion S. Bluford. Of significance, Bluford was the first African-American to fly in space. Eight months later, NASA added Dr. William E. Thornton as a fifth member of the crew to conduct medical investigations on the astronauts to better understand the causes of space motion sickness that was then affecting approximately one-third of all space travelers. (...)

With its first two flights successfully completed, Space Shuttle Challenger was ready to head back into space. As with its previous flights, this one would also be known for several “firsts.” The primary objective of Challenger’s third mission, STS-8, was to deploy the Insat-1B weather and communications satellite for India. The final orbital location of Insat-1B dictated that Challenger launch and land at night, the first time in the Shuttle program. STS-8 was originally planned to fly the second Tracking and Data Relay Satellite (TDRS) to expand space-to-ground communications between Mission Control and orbiting Space Shuttles, but during the launch of the first TDRS on STS-6, its Inertial Upper Stage (IUS) placed it into a stable but incorrect orbit. NASA managers decided to replace the TDRS on STS-8 until the IUS problem could be identified and corrected. Replacing TDRS was the Canadian-built Remote Manipulator System (RMS), or robot arm, and the Payload Flight Test Article (PFTA), an 8,500–pound dumbbell-shaped structure designed to evaluate the dynamics of the RMS.

https://www.nasa.gov/feature/sts-8-the-first-shuttle-night-launch-landingNight Flight of STS-8Aug. 30, 2011

https://www.nasa.gov/multimedia/imagegallery/image_feature_2049.htmlDaniel C. Brandenstein Interviewed by Carol Butler

https://www.nasa.gov/multimedia/imagegallery/image_feature_2049.htmlDaniel C. Brandenstein Interviewed by Carol ButlerKirkland, Washington – 19 January 1999

(...) Butler: I can see where you're coming from with that, definitely. Well, moving into the flying point of view, you were selected as pilot for STS-8. When did you find out that you were going to be on the crew? What were your thoughts at that time?

Brandenstein: I think it was about nine months before the flight. I don't specifically remember. It always started with, "There's a call over at Mr. Abbey's office." The first six flights had been assigned, and they were all experienced, people that had been around the office a long time. Nobody from our class had flown that. But it was hoping and guessing and rumblings like that, starting with 7, 8, and on, that they'd be picking up some of the new class and stuff.

So I got called over one day and they said that I was going to be Dick [Richard H.] Truly's pilot and was going to fly STS-8. That was obviously great. I was excited about that. That's what you wanted to do. One of the really neat things about it, that was going to be a night launch and a night landing. What drove that was, we were launching a satellite for India, and to get it in the proper place, you kind of worked the problem backwards. Okay, they want the satellite up here, so then you've got to back down all your orbital mechanics and everything, and basically it meant we had to launch at night. The fact we launched at night meant that we would end up landing at night. Just, once again, the way the mission worked out.

So that's pretty early in the program to try something like that. I mean, Dick Truly and I had both done night carrier landings, and the way the Shuttle flies, approaches the end of the runway, and doing that at night, we kind of looked at each other and said, "Oooh. This is going to be interesting."

So we got very much involved in developing a lighting system to enable us to safely land at night. We had other people, and once again it was the job of a technical assignment of somebody in the office, kind of like a support crew. We were out of the support crew business by that time, but the crew didn't have enough time to focus just on that, although we got very much involved because we were obviously the ones doing it first. But [Karol J.] Bobko and then Loren [J.] Shriver and then Mike [Michael J.] Smith were all involved in developing the night lighting system, so we went through a rather long evolution of flood lights and spotlights and flares and whatnot, trying to develop some way to give us the visual cues we needed to make a successful night landing.(...)

https://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/BrandensteinDC/brandensteindc_1-19-99.htmCelebrating Guy Bluford's Historic First FlightAug. 30, 2018

https://www.nasa.gov/image-feature/celebrating-guy-blufords-historic-first-flightGuion S. Bluford, Jr. Interviewed by Jennifer Ross-Nazzal

https://www.nasa.gov/image-feature/celebrating-guy-blufords-historic-first-flightGuion S. Bluford, Jr. Interviewed by Jennifer Ross-NazzalHouston, Texas – 2 August 2004

(...) We had a telecom with President Ronald Regan during the flight. He praised us on our accomplishments and wished us well for the remainder of the flight. We also had daily messages from the families and the CapComs kept us appraised as to what was going on, on the ground. During our flight, the CapCom kept me abreast on how Penn State was doing in football and how the Philadelphia Phillies were doing in baseball. Each morning we were awakened by a school song. The Penn State song was played on flight day four. During the mission, we were informed about the shooting down of the Korean airliner over China. This was good for us to know, as we prepared for our on-orbit news conference with the press. During the mission, Dick Truly told me he was leaving the astronaut office after this flight to become Commander of the Naval Space Command, and my wife sent me a message saying that we had termites in our house. Overall the mission went well and we accomplished all of our flight goals.

On flight day five, we configured Challenger for the flight home. The mission seemed to go faster than we had wanted it to and all of us were hoping that we would have the chance to fly again. We rotated the vehicle so that it was flying backwards; we performed the deorbit burn, and then we rotated the vehicle so that it was facing forward and re-entered the Earth’s atmosphere. As we re-entered the Earth’s atmosphere, we began to feel the effects of gravity and see the fiery plasma of hot air burn outside the front windows of the Orbiter. Dale took pictures of the hot plasma as it enveloped us during entry, and he would occasionally hand me the camera. I could feel the camera getting heavier and heavier as we got closer to home. Dick flew us home, and we landed at Edwards Air Force Base a little after midnight on the sixth day. There was an enthusiastic crowd to greet us at our brief post flight press conference. We joined up with our wives, who were waiting for us, and NASA flew us back to Houston. (...)

https://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/oral_histories/BlufordGS/BlufordGS_8-2-04.htmhttps://www.jsc.nasa.gov/Bios/htmlbios/bluford-gs.htmlhttps://www.biography.com/people/guion-s-bluford-213031