Tytuł zmieniony z [AS] Starliner Clears Pad Abort Test as ULA Rolls Out Rocket for Dec 17 Orbital

====

Boeing Folds SLS, CST-100 Space Capsule into New DivisionJeff Foust February 18, 2015 [SN]

Boeing's commercial crew capsule CST-100. Credit: Boeing

Boeing's commercial crew capsule CST-100. Credit: BoeingWASHINGTON — Boeing Defense, Space and Security announced Feb. 11 that it is consolidating several of its aerospace development programs, including the Space Launch System heavy-lift rocket and CST-100 commercial crew vehicle, into a new organization intended to improve management of those efforts.

https://spacenews.com/boeing-folds-sls-cst-100-space-capsule-into-new-division/Curtiss-Wright To Complete CST-100 Avionics SystemWarren Ferster April 8, 2015 [SN]

Click to share on X (Opens in new window)Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)Click to share on Clipboard (Opens in new window)

CST-100 cockpit

Boeing's Chris Ferguson inside a CST-100 cockpit simulator. Credit: NASA/Bill Stafford

WASHINGTON — Curtiss-Wright Defense Solutions will finish developing and deliver a key flight data handling system for Boeing’s CST-100 commercial astronaut taxi under a contract modification announced by the Ashburn, Virginia, company March 31.

====

Starliner Clears Pad Abort Test as ULA Rolls Out Rocket for Dec 17 Orbital Flight TestBy Mike Killian, on November 4th, 2019

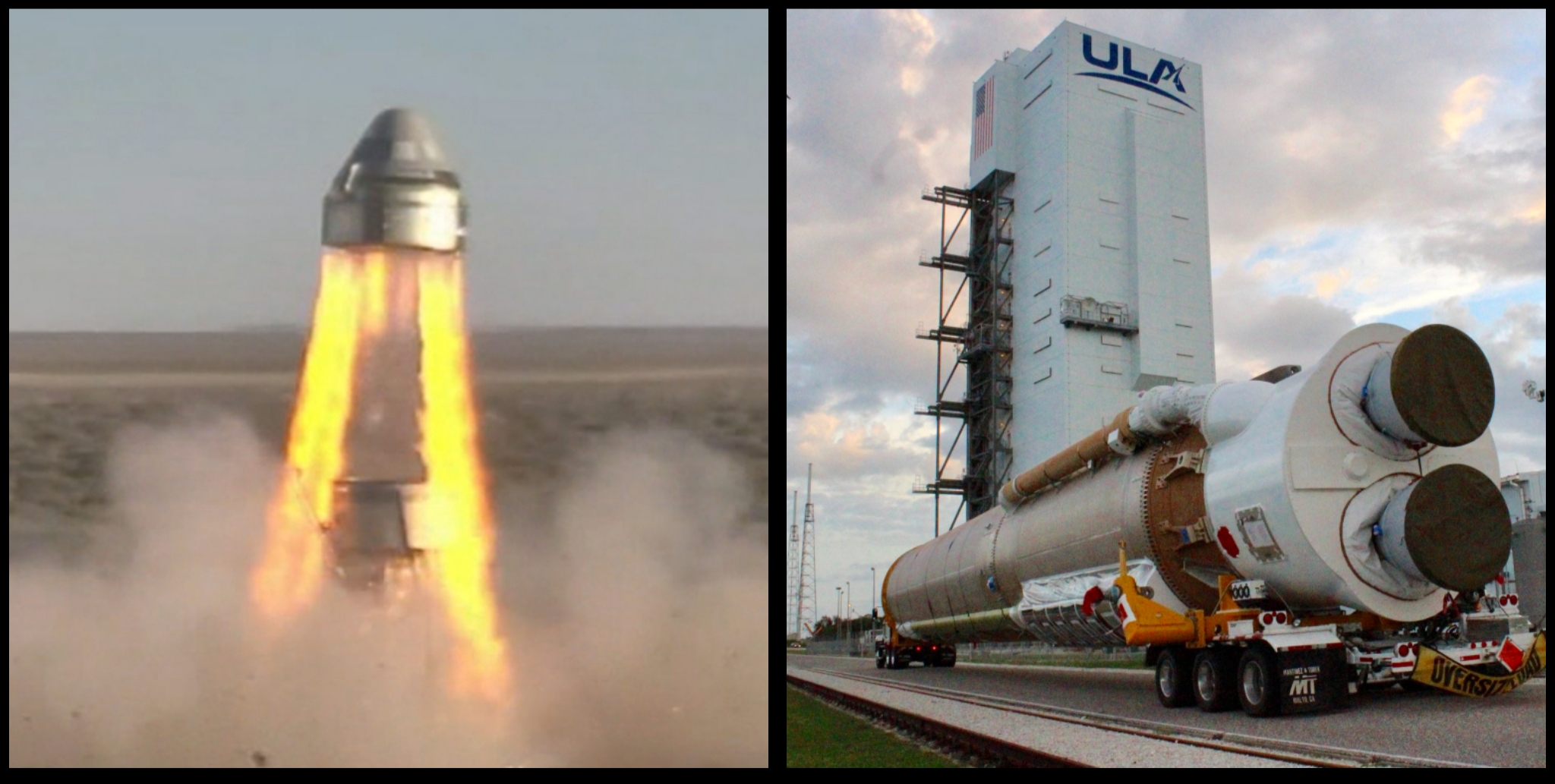

This morning, Boeing conducted the first major flight test of their new CST-100 Starliner crew capsule, flying off a launch stand at White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico for a pad abort test to demonstrate and prove it can safely escape an exploding rocket to save its crew.

This morning, Boeing conducted the first major flight test of their new CST-100 Starliner crew capsule, flying off a launch stand at White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico for a pad abort test to demonstrate and prove it can safely escape an exploding rocket to save its crew.

Source: https://www.americaspace.com/2019/11/04/starliner-clears-pad-abort-test-as-ula-rolls-out-rocket-for-dec-17-orbital-flight-test/

Część do skasowania:

It was their first flight test under a $4.2 billion contract for NASA’s Commercial Crew Program, and will provide Boeing and NASA with loads of data to help evaluate and verify the performance of Starliner’s abort system, before NASA will certify it and board astronauts for missions to and from the International Space Station beginning next year.[/size]

Watch Starliner conduct its pad abort test, a major milestone on the path to earning certification from NASA to begin launching astronauts next year.

For the test, Starliner’s four launch abort engines (LAE) ignited with a combined 160,000 pounds of thrust to send the vehicle and its test dummy rider skyward. Five seconds later the abort engines shut off as planned, as control thrusters took over steering for the next five seconds, as Starliner pitched around and rotated into position for landing as it neared its peak altitude of 4,500 feet.

However, as the landing sequence played out only two of three main parachutes deployed. And while that may seem like cause for concern to armchair expert enthusiasts and the general public, it isn’t, because the system was designed to land fine fine under two parachutes anyway.

Only two of three parachutes deployed in Boeing’s Pad Abort Test of its CST-100 Starliner spacecraft over the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico. The system is designed to land just fine in the event of losing a parachute, and both NASA and Boeing consider the test a success, paving the way to an uncrewed Orbital Flight Test as soon as Dec 17 from Cape Canaveral. Photo: NASA / Boeing

“We did have a deployment anomaly, not a parachute failure,” explained Boeing after the flight test. “It’s too early to determine why all three main parachutes did not deploy, however, having two of three deploy successfully is acceptable for the test parameters and crew safety. At this time we don’t expect any impact to our scheduled Dec. 17 Orbital Flight Test. Going forward we will do everything needed to ensure safe orbital flights with crew.”

“Two opening successfully is acceptable for the test perimeters and crew safety,” says NASA. It was the first time the full sequence was demonstrated as on-flight hardware.

Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner landed gently under two parachutes and airbags in the New Mexico desert in the company’s Pad Abort Test for NASA’s Commercial Crew Program on Nov 4, 2019. Photo: NASA / Boeing

“Tests like this one are crucial to help us make sure the systems are as safe as possible,” said Kathy Lueders, NASA’s Commercial Crew Program manager. “We are thrilled with the preliminary results, and now we have the job of really digging into the data and analyzing whether everything worked as we expected.”

“Emergency scenario testing is very complex, and today our team validated that the spacecraft will keep our crew safe in the unlikely event of an abort,” said John Mulholland, Vice President and Program Manager, Boeing’s Commercial Crew Program. “Our teams across the program have made remarkable progress to get us to this point, and we are fully focused on the next challenge—Starliner’s uncrewed flight to demonstrate Boeing’s capability to safely fly crew to and from the space station.”

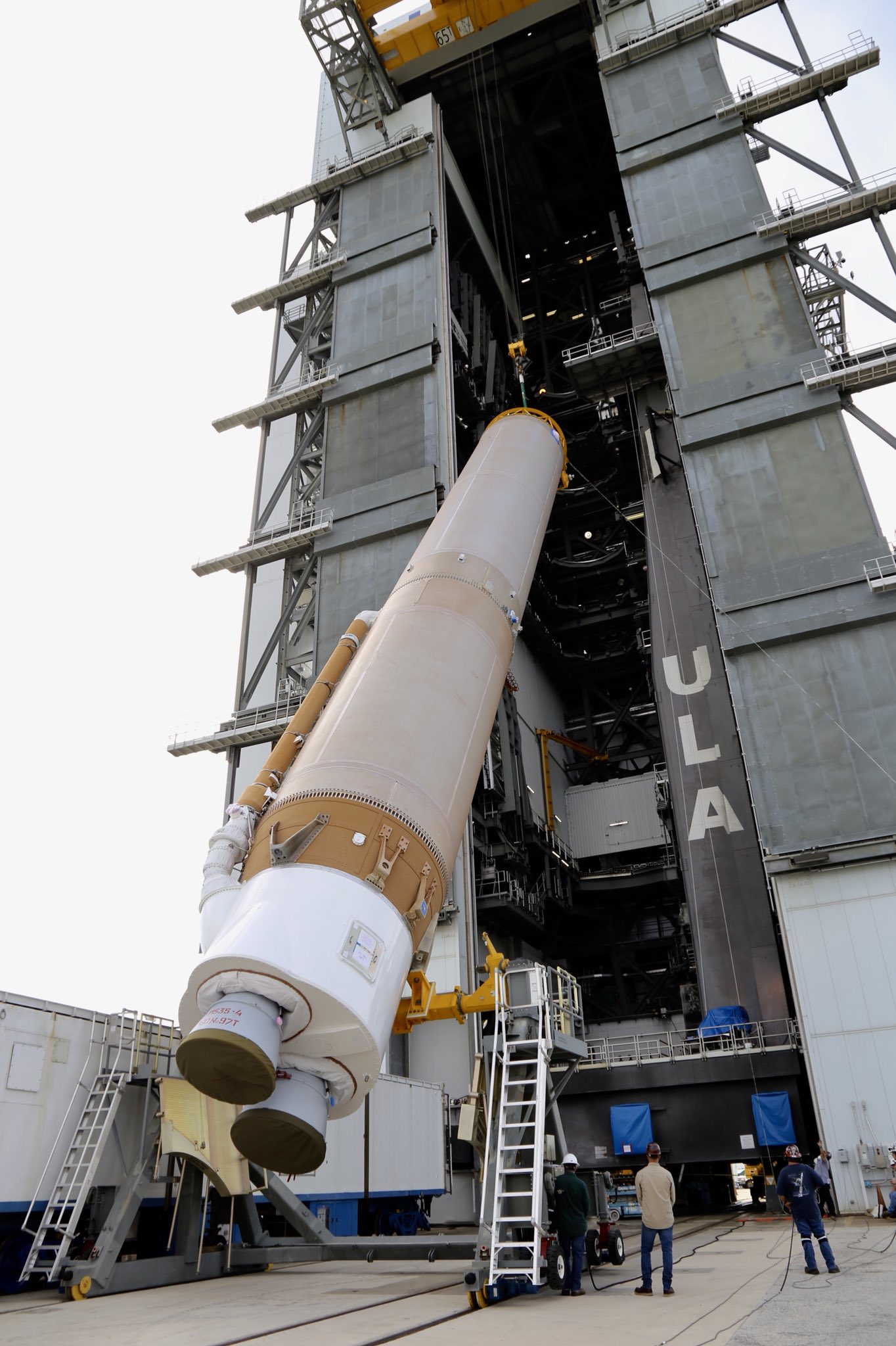

ULA hoisting the Atlas V rocket upright at their Vertical Integration Facility at Launch Complex 41, kicking off the launch campaign for Boeing’s uncrewed Starliner Orbital Flight Test as soon as Dec 17. Photo: ULA

Meanwhile, 2000 miles away in Florida United Launch Alliance (ULA) is busy getting Starliner’s first rocket ride to space ready for that Dec 17 target launch. Overnight, the Atlas V rocket was moved from a holding bay at ULA’s Atlas Spaceflight Operation Center (ASOC) and hauled horizontally by semi-truck nearly four miles to Launch Complex 41’s Vertical Integration Facility (VIF). Two cranes grappled both ends of the 107-foot-long rocket, lifting and rotating it upright, then hoisting it into the 30-story-tall assembly building and placed on its Mobile Launch Platform (MLP).

With the booster now at its launch site, ULA teams will now attach two solid rocket boosters to the rocket (brought in 1 by 1), before hoisting the Centaur upper stage to attach atop the rocket.

The Orbital Flight Test Starliner getting ready for propellant loading ahead of rollout to the Atlas-V launch site for its upcoming Orbital Flight Test. Photo: Boeing

At the same time, the Starliner for December’s uncrewed Orbital Flight Test is undergoing propellant loading, and will be transported to the VIF at LC-41 to meet its rocket in the next couple weeks.

Following that, ULA will roll out the fully-assembled, 172-foot-tall rocket with Starliner to the nearby launch pad to conduct an Integrated Day-of-Launch Test (IDOLT), also known as a Wet Dress Rehearsal (WDR), where launch teams fuel the rocket stages and go through the launch countdown same as launch day, without actually igniting the engines.

[/i]